Prof Zohar Amar is demonstrably wrong about tel Arad, ‘kaneh bosm’ and the ancient use of cannabis

CANNABIS CULTURE – Zohar Amar, is a professor in the Department of Land of Israel Studies at the religious-Zionist Bar-Ilan University. His specialty is in identifying the plants of the ancient Levant, and he is highly respected in his field. ‘The Book of Incense’ by Amar has been widely acclaimed. Recently Prof. Zohar dismissed the claim the ancient Israelites used cannabis.

In a response to the discovery of cannabis resins on an altar at the site of an 8th century BCE temple at tel Arad, Jerusalem, Prof. Amar commented on the implications of the find and the linguistic theory of Sula Benet that the Hebrew ‘kaneh bosm’ originally identified ‘cannabis’. The article appeared In the Makor Rishon, a Hebrew language Israeli weekly newspaper, which was graciously translated from the Hebrew for me by Avi Levkovich. In the June 12th, 2020 edition Prof Amar explains [I have numbered the paragraph for my responses]:

1) The Israelites did not smoke cannabis in the temple and cannabis is not “kaneh bosm”. There is no evidence of its use in the temple in Jerusalem. Quite the opposite: Judaism abhors intoxicating its believers.

2) Recently it was announced that during an inspection of an altar located in Tel Arad remains of frankincense and cannabis were found. The altar was located in the temple of an Israeli citadel that probably dates to the ninth century BC. A raised platform and a tomb were also found in the temple complex. Following this discovery, the researchers determined that the use of cannabis for worship was not only local but also prevalent in the central worship in the temple in Jerusalem. Meanwhile, the claim that cannabis is the “kaneh bosem” (aromatic cane) which was used for the purposes of worship in the temple was revived. In my humble opinion, these interpretations are unfounded and stem from a confusion between concepts or perhaps the needs of an academic rating.

3) The interpretation according to which cannabis is the “kaneh bosem” began as “Vort” i.e a nice little insight, a linguistic refinement resulting from a chance similarity of sounds, but without any scientific grip. As is the way of urban legends, they took hold among the masses and over time penetrated the world of research as well. And this is how a theoretical interpretation may become a “scientific truth”. This is one of the products of the open pit field of the biblical plant identification field that sometimes relies on unfounded hypotheses.

4) ”Kaneh bosem” was used as one of the components of the anointing oil in which the holy vessels and the priests were anointed (Exodus 30:23-25) and is not at all related to the incense ingredients that were incensed in the temple (Exodus 30:34; tractate Keritot 6a). This ingredient cannot be cannabis for several reasons: the plant and its products are not defined as perfumes and are not mentioned in the use of scent and incense in all cultures of the ancient world. Also, it does not appear in this context in any of the ancient identification traditions or in the authorized studies that deal with the identification of biblical plants.

5) Furthermore, the claim that the use of cannabis incense in Tel Arad for the purpose of intoxicating the worshipers in the temple to create a sense of transcendence is part of a common phenomenon throughout Judea and even in the temple in Jerusalem – is groundless. Although the use of narcotic substances such as opium was known in pagan worship, the official Jewish position denied this outright. Even drinking wine and other fermented drinks by the priests was considered a severe prohibition and for this it is said in the Torah that a distinction must be made between “impure and pure” (Leviticus 10:8-11). In Yerushalmi Talmud “Avoda zarah”, the use of opium is prohibited “because of the danger”.

6) A finding of cannabis in Tel Arad indicates that it is what is called in the bible “worship in the Bamot” that is considered a halachic deviation from the pure Israeli faith. There is also no echo of such use in the temple in Jerusalem from the scriptures, the jewish literature or from any other findings. Due to the idolatrous-themed activity and the desire to have one central worship in Jerusalem, the activity of the temple at Tel Arad was cancelled, probably as part of Hezekiah’s religious reform (2 Kings 18:4). This points to the opposite conclusion: the Israeli faith rejected the use of cannabis or any narcotic substance for the purpose of the work.

—————

Prof. Amar is wrong on a number of points. In regards to paragraph 1, it is important to note that ritual use of psychoactive substances would likely not be thought of as ‘intoxication’ in the same sense as we think of it now. Also, we are dealing with a long history here, and what might have been ok for one generation may not have been ok for another. Both tel Arad and the references to kaneh and kaneh bosm, attest to this factor. Tel Arad was ‘cancelled’, the preservation of its relics is largely due to the latter being knocked over and buried in a day, with a no floor placed over them. This is thought to be due to the ‘reforms’ of Hezekiah or Josiah. Likewise with the kaneh references, we are dealing with a substance that was initially a prized item of worship (Exodus 30:23), but in it’s later reference, coldly rejected as an offering due to its ‘foreign’ association (Jeremiah 6:20).

Also in regards to intoxication we have the example of Purim day, a festive meal called the Se’udat Purim is held. There is a longstanding custom of drinking wine at the feast. On Passover, the four cups of wine are for joy and for sanctification, “Rava said: It is one’s duty [levasumei], to make oneself fragrant [with wine]on Purim until one cannot tell the difference between ‘arur Haman‘ (cursed be Haman) and ‘barukh Mordekhai’” (blessed be Mordecai)” (Babylonian Talmud). This does indeed sound like intoxication, and the festivities of these events are well known.

In Paragraph 2, Prof. Amar refers to the findings of the 2020 paper Cannabis and Frankincense at the Judahite Shrine of Arad, skimming over the details. Tel Arad is a well known site, and this temple has been moved and rebuilt and is on display in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. It has been considered a miniature version of the Holy of Holies in ancient Jerusalem through similarities in it’s design and Biblical descriptions of the design of temple in Jerusalem. As well an inscription was found on site that referred to its as a ‘house of Yahweh’. This temple would have been in use prior to the reforms that saw the removal of cultic object associated with Asherah, such as the asherim removed from the temple and the brazen serpent, which Hezekiah destroyed because the people burned incense to it 2 Kings 18:4, as well as the removal of all places of worship besides the main temple in Jerusalem, centralizing the where offerings could be received, along with wealth and control.

Cannabis and Frankincense at the Judahite Shrine of Arad, Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University Volume 47, 2020

In Paragraph 3, Amar indicates that the basis of the claim that kaneh bosm is cannabis is purely phonetic, and the similarity in sound to our own term ‘cannabis’. However this similarity is more direct with contemporary names for cannabis in the surrounding region, as well as the later Mishnic term for cannabis. Here the similarities go far beyond the merely phonetic, and we see comparable use in place as well. It is qunnabu in Assyrian, kenab in Persian, kannab in Arabic and kanbun in Chaldean. In this regard it should be noted that phonetically kaneh bosm, could also be translated as qaneh bosm, and likewise the Assyrian qunnabu, can also be translated as kunnabu, in both cases the first letter is a hard Q sound, with no ‘u’ . Assyrian references refer to it’s use specifically in ointments, incenses and for the sacred rites.

In the second quarter of the first millennium BCE, the “word qunnabu (qunapy, qunubu, qunbu) begins to turn up as for a source of oil, fiber and medicine” (Barber 1993). In our own time, numerous scholars have come to acknowledge qunubu as an early reference to cannabis. As Prof. of Botany Richard Evens Schultes and father of LSD Dr Albert Hoffman have noted “It is said that the Assyrians used hemp as incense in the seventh and eighth century before Christ and called it ‘Qunubu’”( Schultes & Hoffman 1979). Recipes for cannabis, qunubu, incense, regarded as copies of much older versions, were found in the cuneiform library of the legendary Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, (b. 685 – ca. 627 BC, reigned 669 – ca. 631 BC). Cannabis was not only sifted for incense like modern hashish, but the active properties were also extracted into oils. “Translating ‘Letters and Contracts , no.162’ (Keiser, 1921), qu-un-na-pu is noted among a list of spices (Scheil, 1921)(p. 13), and would be translated from French (EBR), ‘(qunnapu): oil of hemp; hashish.’”(Russo, 2005). Note here the resins on the altar from tel Arad are thought to have been from hashish or another cannabis resin product.

Records from the time of Ashurbanipal’s father Esarhaddon,(reigned 681 – 669 BC) give clear evidence of the importance of such substances in Mesopotamia, as cannabis, ‘qunubu‘ is listed as one of the main ingredients of the pivotal ‘Sacred Rites’. This use is contemporary to that indicated in the Bible, and it should be noted both father and son appear in the Old Testament narrative (Esarhaddon II Kings 19:37, Isaiah 37:38, and Ezra 4:2: Ashurbanipal Ezra 4:10)

In a letter written in 680 BCE to the mother of the Esarhaddon, reference is made to qu-nu-bu,. In response to Esarhaddon’s mother’s question as to “What is used in the sacred rites”, a high priest named Neralsharrani responded that “the main items…. for the rites are fine oil, water, honey, odorous plants (and) hemp [qunubu]”.

Cannabis was clearly an important ritual implement from early on in Mesopotamia. Professor George Hackman referred to 4000 yr old inscriptions indicating cannabis in Temple Documents of the Third Dynasty of Ur From Umma. The inscription below is described as a “Memoranda of three regular offerings of hemp”(Hackman, 1937).

In The Cults of Uruk and Babylon, Marc Linssen notes another cultic use of cannabis, “some of the known aromatics, such as … qunnabu… are mentioned in the… Kettledrum ritual text TU 44, IV, 5ff…. In the list of ingredients for this rite 10 shekel qunnabu– aromatics”( Linssen, 2004).

In Paragraph 4, Prof. Amar’s case really falls apart, and I have to question here, did he even research cannabis’ history in the ancient world? Amar states: “‘Kaneh bosem’ was used as one of the components of the anointing oil in which the holy vessels and the priests were anointed (Exodus 30:23-25) and is not at all related to the incense ingredients that were incensed in the temple (Exodus 30:34; tractate Keritot 6a).” Here Amar makes the assumption that the Exodus recipe defines all use of kaneh in the bible. This is not the case, and I would argue that it is the references in Isaiah and Jeremiah, which really identify it with the use indicated at tel Arad. As well, the temple incense recipe in Exodus included a secret herb, which went unnamed, which caused the smoke to raise in a pillar, which is the way cannabis is used, and Moses is also instructed to anoint the later of incense.

In relation to this Dr. Yoseph Glassman states that Moses ben Nachman, commonly known as Nachmanides, and also referred to by the acronym Ramban a leading medieval Jewish scholar, Catalan rabbi, philosopher, physician, kabbalist, and biblical commentator, indicated that the 12th ingredient of the temple incense, a secret ingredient, the malashon, which caused it to rise as a pillar was ‘kaneh bosm‘ cannabis .

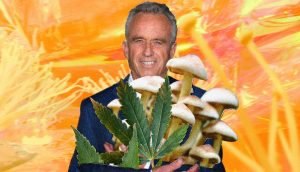

A High priest about to hotbox the inner temple at tel Arad. Cannabis resin was recovered rom the smaller altar and frankincense from the larger.

It is also worth noting here that THC is fatty soluble and can pass through the skin, which is itself an organ. Health Canada has done scientific tests that show transdermal absorption of THC can take place. The skin is the biggest organ of the body, so of course considerably more cannabis is needed to be effective this way, much more than when ingested or smoked. The people who used the Holy Oil literally drenched themselves in it. Based upon a 25mg/g oil Health Canada found skin penetration of THC (33%). “The high concentration of THC outside the skin encourages penetration, which is a function of the difference between outside and inside (where the concentration is essentially zero)” ( James Geiwitz, Ph.D, 2001). I talked to Dr. Geiwitz personally and he told me that he felt this offered strong evidence for the potential psychoactive effects of the Holy Oil.

We also have contemporary use of such topical preparations. In Studies on Neo-Assyrian Texts II: “Deeds and documents” from the British Museum (1983) Frederick Mario Fales, translates the following ancient cuneiform verse (No. 12. BM103205. Copy: p. 252) regarding the Goddess Ishara and qunubu cannabis:

The salve of Ishara

is cannabis;

The salve of Ishara

is cannabis:

From the mouth of Qisirayyu I hear so

Assyriologist Erica Reiner reveals a connection between the goddesses Ishara and Ishtar and cannabis in reference to the: “herb called Sim.Ishara ‘aromatic of the Goddess Ishtar,’ which is equated with the Akkadian qunnabu, ‘cannabis’, [which]may indeed conjure up an aphrodisiac through the association with Ishara, goddess of love, and also calls to mind the plant called ki.na Ishtar” (Reiner, 1995).

The following passage regarding the topical application of cannabis is very interesting when compared alongside the use of the cannabis infused “Holy Oil” for similar purposes amongst ancient Hebrew figures. “An Assyrian medical tablet from the Louvre collection (AO 7760)(Labat, 1950)(3,10,16) was transliterated as follows…,‘So that god of man and man should be in good rapport:—with hellebore, cannabis and lupine you will rub him.’ (Russo 2005). Such topical preparations were also used medically.

A 2002 edition of the Compte Rendu, Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, a journal from the Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale (RAI) the annual Assyriological Conference, in a paper on hashish and opium noted “Qunnabu or qunnubu has emerged as the best candidate for identifying cannabis.” The respected journal gives us some insights into the methods and extent of its use: “…A Neo-Assyrian recipe for making perfume speaks of steeped cannabis; a smoking pool is mentioned immediately in front of it. The context is unfortunately destroyed … cannabis together with other aromatics. Oil and wash was used in an unspecified ritual process…. Not insignificant quantities of this plant are delivered to the large temples – Eanna and Ebabbar.” Likewise the The Routledge Companion to Ecstatic Experience in the Ancient World’ records: “Akkadian qunnabu is almost exclusively attested as one ingredient among many in incense blends and perfume mixtures used in the religious cult…” (Böck, 2022). ‘

However, regardless of this information, or ignorant of it, Prof. Amar makes the statement that “This ingredient [kaneh bosm] cannot be cannabis for several reasons: the plant and its products are not defined as perfumes and are not mentioned in the use of scent and incense in all cultures of the ancient world.” This has been shown to be demonstrably false, above are noted contemporary references to cannabis in such preparations in the ancient world, Essarhaddon and Ashurbanipal both appear in the Bible in fact. I am saying here unequivocally qunnabu is the phonetic Assyrian equivalent of the Hebrew ‘kaneh Bosm‘ and is used in the same way as an ointment and incense.

Prof Amar adds “Also, it [kaneh bosm] does not appear in this context in any of the ancient identification traditions or in the authorized studies that deal with the identification of biblical plants.” Well, there is mention with other candidates from Aryeh Kaplan in The Living Torah, but for the most part, Amar is right. Kaneh bosm has been discounted by Biblical scholars, to their own discredit. Now we have clear evidence of the ritual use of cannabis the only ancient Hebrew temple site recovered and none of these Biblical scholars predicted such use, or have really done much to place it in context. Amar fails here completely.

The Living Torah entry on kaneh bosem, includes cannabis as a candidate.

In regards to Paragraph 5, Prof Amar writes “the claim that the use of cannabis incense in Tel Arad for the purpose of intoxicating the worshipers in the temple to create a sense of transcendence is part of a common phenomenon throughout Judea and even in the temple in Jerusalem – is groundless. Although the use of narcotic substances such as opium was known in pagan worship, the official Jewish position denied this outright.” Here Amar takes a step back from actual history into his own religious beliefs. There was no ‘Jewish’ religion at the time the tel Arad temple was in use, historically the whole region was polytheistic, and as many now know Yahweh was coupled with the Goddess Asherah, who was also worshipped in tel Arad. The religious and cultural transition from polytheism to monotheism plays an important role here in regards to what happened at tel Arad and with the later rejection of kaneh as recorded in the Hebrew Bible. It also explains how a substance that was once holy came to be rejected by the later development of monotheistic Judaism.

I have looked at a lot of criticisms of the linguistic theory that the Hebrew kaneh bosm identifies cannabis, and I often find it is based on a reading of only the first of the 5 references, that being Exodus 30:23 and its identification in the Holy oil.

I would argue that the other references are more important in regards to what we now know from archaeological evidence as well.

Let us look for example at the reference in Isaiah 43:23-24

“I have not burdened you with offerings, or wearied you with frankincense. You have not bought me sweet smelling kaneh with money, or satisfied me with the fat of your sacrifices. But you have burdened me with your sins; you have wearied me with your iniquities.”

Interestingly here, Yahweh laments at the lack of kaneh and frankincense, this fits well with tel Arad and its altars, one for frankincense and one for cannabis.

I would also say that the reference to ‘sins’ and ‘iniquities’ in this verse tie it with another verse, where these terms also appear, Isaiah 6: 4-7, and the desire here for oracular incense was appeased!

“…the temple was filled with smoke.

“Woe to me!” I cried. “I am ruined! For I am a man of unclean lips, and I live among a people of unclean lips, and my eyes have seen the King, the Lord Almighty.”

Then one of the seraphim flew to me with a live coal in his hand, which he had taken with tongs from the altar. With it he touched my mouth and said, “See, this has touched your lips; your iniquity is taken away and your sin atoned for.”

In Isaiah 43 God laments about being burdened with sins and iniquities without the offering of kaneh and frankincense, In Isaiah 6, we see these same appeased with an offering of incense with Isaiah taking an inhalation right from a coal from the altar!

However in Jeremiah 6:20 we see such offering outright rejected, and the former holy oil ingredient, and one which in Isaiah god angers at not receiving with frankincense, is rejected, and here again with frankincense, as with the cancelled altars at tel Arad!

Jeremiah 6:20

What do I care about frankincense from Sheba or sweet smelling kaneh from a distant land? Your burnt offerings are not acceptable; your sacrifices do not please me.”

I would suggest here the rejection is tied up with references in Jeremiah 44, and the worship of Asherah as the Queen of Heaven, and this was likely an issue with tel Arad as well. After escaping the Fall of Jerusalem while in Egypt, Jeremiah blames them for the fall of Jerusalem for burning incense to other gods. The people’s response is telling:

“We will certainly do everything we said we would: We will burn incense to the Queen of Heaven and will pour out drink offerings to her just as we and our ancestors, our kings and our officials did in the towns of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem. At that time we had plenty of food and were well off and suffered no harm. But ever since we stopped burning incense to the Queen of Heaven and pouring out drink offerings to her, we have had nothing and have been perishing by sword and famine.” The women added, “When we burned incense to the Queen of Heaven and poured out drink offerings to her, did not our husbands know that we were making cakes impressed with her image and pouring out drink offerings to her?”

Asherah was also known as ‘the lady of the serpent’ and among Hezekiah’s reforms in the temple was the destruction of the ‘brazen serpent’ because the people ‘burned incense unto it’.

This all fits with the time period of the cancelation of tel Arad, and we know Asherah was worshipped there form cultic items found.

Also worth noting is that in Jeremiah 6:20 and the reference to kaneh from Ezekiel 27:19, kaneh is described as coming from a foreign land and as an item of trade, and this is the case for the cannabis at tel Arad, researchers suggest it arrived as an item of trade.

Further connecting it with the Goddess, is the reference in the Song of Songs, a polytheistic Hebrew king who built the original temple, but was condemned for worshipping the Goddess and burning incense on the High Places. For more than a century it has been suggested that Solomon’s Songs were originally a Hebrew version of the Heiros Gamos or ‘Sacred Marriage, where the conceptual rights of the God and Goddess were rituals enacted by human counterparts, to ensure the fertility of the people and the land.

“How delightful is your love, my sister, my bride! How much more pleasing is your love than wine, And the fragrance of your ointment than any spice!… The fragrance of your garments is like that of Lebanon… Your plants are an orchard of pomegranates,”With choice fruits, with henna and nard, Nard and saffron, kaneh [cannabis]and cinnamon, with every kind of frankincense tree… “

– Song of Songs 4:8-14

Like the ointment of Ishara we see here that the ointment is more pleasing that wine! Interestingly the suggestion that the worshippers of Asherah used cannabis has been suggested. Robert Graves wrote in an article in the 1970 edition of The Atlantic:

Taking cannabis is indeed an ancient enough practice; cannabeizein, “to smoke pot,” appears in the ordinary Classical Greek dictionary. Presumably its fumes were absorbed through the pores of the skin when the cannabis itself was smoked over a low fire – the pot taker crouching over it clad only in a poncho. This at least seems to have been how the Ashera priestesses of the pre-Reformation Temple at Jerusalem impregnated their skins with the holy incense, which was mixed with other perfumes (Graves, 1970).

Unfortunately, Graves gave no indication for the origins of this claim and I cannot find anything regarding this, beyond his statement. However, what is interesting is that Graves had a very close relationship with Rapahel Patai, author of The Hebrew Goddess (1967). In fact in the early 1960s the two wrote a book together, The Hebrew Myths (1964). However this connection is strengthened by known references to cannabis in the worship of Ishtar, Ishara and Inanna, and it seems, like other aspects to have been part of a pattern of Near Eastern Goddess Worship.

Through its association with the Goddess, and former wife of Yahweh, along with the polytheism of the past, cannabis came to be rejected. The new monotheism was more about organizational rule and structure, and left little room for shamanic revelation. The age of the prophets also came to an end here.

This situation answers paragraph 6 of Prof Amar’s comments. However, he fails to see that even in the Biblical accounts of Kings and Chronicles, polytheism, was the norm. Both tel Arad and contemporary inscriptions indicate Yahweh was coupled with the Goddess Asherah. Hezekiah’s reforms included removing her cultic items from the temple in Jerusalem, and after his reign, the people returned to her worship, and his grandson Josiah had to pick up the torch of monotheism. Monotheism, was the new innovation, these were not reforms, but a new way of governing and control. Indeed there was a need to consolidate, under the encroachment of Assyrians and then Babylonians. However monotheism, and anything representing what might be called the Jewish religion, would not take hold in the area until after the Persian return.

So what happened with cannabis? How was the identity of kaneh bosm lost? Sula Benet Suggests that a mistranslation occurred when the Hebrew texts were translated into Greek for the Septuagint, rendering it as calamus, and this mistranslation followed into other translations, with various variations. Other mistranslations and misidentifications of plants are known as the texts were translated from Hebrew to Geek.

However, Sula Benet, noted that in the Hebrew world, kanabos, for ‘cannabis’ appears in the Mishna, the oldest authoritative post biblical collection and codification of Jewish oral laws, systematically compiled over a period of about two centuries and given final form early in the 3rd century CE. Benet asserts that kanabos derived from kaneh bosm. “In the course of time, the two words ‘kaneh‘ and ‘bosm‘ were fused into one, ‘kanabos‘ or ‘kannabus,’ known to us from Mishna, the body of traditional Hebrew law” (Benet, 1975). This term appears in a number of texts from that period and later. However Rav Pappah’s 4th century and Rashi’s tenth century CE use of the same term, kanabos, tends to be unconvincingly discounted as a later Hebrew version of the Greek, ‘kanabis’ (cannabis) that was adopted during the Hellenistic period, rather than a carryover of the terms kaneh bosm or kaneh from the earlier Hebrew. This may have been a valid argument prior to the discovery of cannabis resins at the shrine in tel Arad. However, the case for a Greek origin of the Mishna kanabos loses ground now that we have direct evidence for cannabis use during the composition period of the Hebrew Bible. To suggest that the Mishna term kanabos was derived from the Greek kannabis, would now require the discovery of an alternative ancient Hebrew name for cannabis, unrelated to kaneh bosm, that was replaced by the Greek term, to be believable. Such a move would have garnered discussion from the Rabbis.

Sula Benet (1903-1982)

Regardless of the controversy regarding the identification of the origins of the Mishna term kanabos, with kaneh bosm or Greek kannabis, cannabis was seen as a suitable cloth for ritual attire well into the 16th century. Chapter 9 of the Shulchan Aruch, Code of Jewish Law, records that prayer shawls could be made from wool, silk, flax or hemp. Recently Rabbi Yosef Glassman, summarized “the Talmud does discuss the growing of fields of cannabis, the Shulchan Aruch, Code of Jewish Law, mentions using cannabis for Shabbat wicks, and many sources talk about cannabis as a staple in Jewish clothing, since it doesn’t absorb spiritual impurity… and it… was found to have been used in ancient Israel as an anesthetic, even during childbirth.”

Rabbi and Dr. Yoseph Glassman

As with finds of cannabis resins in ancient Israel, there is also notable archeological evidence for hemp cloth. Hemp fibre has been found in the Levant at the 800 BCE archaeological site of Deir ‘Alla, in a context which implies ritual use, (Boertien 2007). Hemp fibre has also been recovered from the later Talmudic period ‘Hemp in ancient rope and fabric from the Christmas Cave in Israel: Talmudic background and DNA sequence identification’ (Murphy, et. al., 2011).

Currently there is no consensus on what plant kaneh bosm identifies, just a variety of candidates and a debate. Candidates include calamus, schoenus, bark of cinnamon, vetiver, ginger grass, camel grass, lemon grass, fennel, sugar cane and cannabis. However, the evidence sits much more firmly with cannabis than any of these other candidates as we have seen, and the evidence for this goes far beyond the similarity in the cognate pronunciation that was suggested. The new archeological evidence from the 8th century BCE temple site in tel Arad, have reignited the debate regarding kaneh bosm as cannabis. I think when one has seen how seamlessly this etymological evidence fits with tel Arad, most would agree that it clearly settles that debate.

A more thorough discussion of the etymology of kaneh and kaneh bosem can be found in my article Is Dan McClellan Wrong About ‘Kaneh Bosem’ And ‘Christ’?

For a more detailed analysis of how kaneh connects with the findings at tel Arad see my book Cannabis: Lost Sacrament of the Ancient World

Also see this youtube presentation for a synopsis Kaneh Bosm and Tel Arad’s use and Rejection of Cannabis –